Spandita Malik, a passionate designer and photographer from Chandigarh has not only made the city, but the entire country proud of her artistic talent, as her work on gender violence got selected by the much-coveted British Journal of Photography for their annual issue.

Spandita Malik, a passionate designer and photographer from Chandigarh has not only made the city, but the entire country proud of her artistic talent, as her work on gender violence got selected by the much-coveted British Journal of Photography for their annual issue.

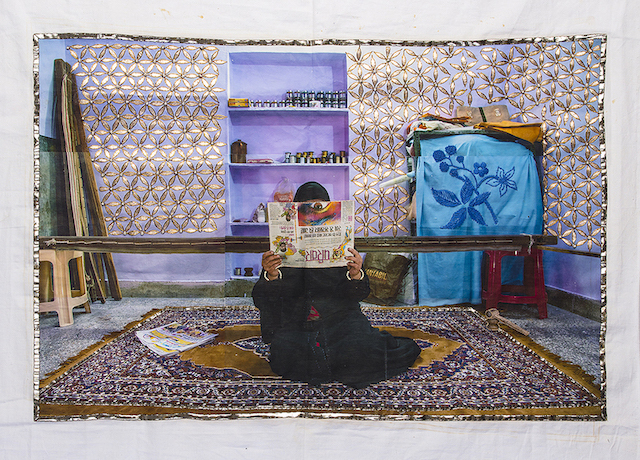

Presently based in New York, Malik has got a rare global recognition by getting selected amongst 18 artists for her unique mixed- media- image- making work on gender violence in her native India. This comes as a part of her latest series Nā́rī (Sanskrit for woman, wife, female or an object regarded as feminine – also meaning sacrifice), which has some of the most powerful portraits of women in India.

Recently graduating from Parsons School of Design with an MFA in Photography after her Fashion Design degree from NIFT, New Delhi, Malik had taken portraits of women in India and printed them on fabric from their various regions.

Her training had engrained a sense of the necessity of working with her hands, that “nothing was finished by a click”. To Malik, a photograph was never a finished product: it needed intervention, tactile manipulation, building on its surface, or scrubbing that same surface away.

An Ongoing Creative Process

The British Journal of Photography, published since 1854, had announced their annual search for emerging photography talent, with their ninth Ones to Watch platform, which is dedicated to celebrating the best emerging talent from across the globe.

The Journal in its foreword of the mega issue said, “For Spandita Malik, the printed photograph is only the beginning of her creative process. By considering texture and embroidery, a craft connected to her exploration of the violence and injustices suffered by women in her native India, she achieves multiple-layered meaning.”

A Colourful Adornment

Giving the conceptual background of her work Malik says that she has tried to involve process of mixed-media image-making that has been brought to bear on extended explorations into misogyny and violence against women in her native India.

“l was in New Delhi right after the major gang rape case of 2012,” she describes. “l think that really influenced me, as a woman, to think about my position in the society that I grew up in. And I think that has influenced a major chunk of my practice.”

In grad school, Malik researched rape culture in India, learning all she could about laws, statistics and support groups. She began to incorporate this research into early projects such as Being A Woman, a mixed-media photographic project comprising her own photographs and newspaper articles which she sewed into with red thread, underlining particularly egregious examples of misogyny.

Explaining the significance of Malik’s unique work, the Journal said that instead of addressing the darkness of these women’s circumstances directly, the colourful adornment of Malik’s collaborative portraits speaks of feminine resistance and survival.

“This is something that women have been passing on for generations,” Malik describes.” I started thinking of embroidery as a language that we’ve created for ourselves. It’s something that we can write through, and only we understand, and we’ve been passing it on as a lineage.”

Bright and Beautiful

Malik began to make photographic portraits of the women she met in their homes, consciously choosing the spaces where they felt most comfortable. She printed the portraits onto fabric specific to each woman’s respective region, and then gave them back to the women to stitch their own portrait upon it, however they chose. Despite the context of violence that informs the work (many of the women are survivors of domestic abuse, using embroidery as a means of gaining economic independence), the images are bright and beautiful. Malik’s striking portraiture is ornamented with vibrant, patterned stitching.

The fact that the women are actively engaged in the creation of their own image, choosing how they wish to be depicted, is essential, as is the gendered specificity of the medium with which they do so. “This is something that women have been passing on for generations,” Malik describes.” I started thinking of embroidery as a language that we’ve created for ourselves. It’s something that we can write through, and only we understand, and we’ve been passing it on as a lineage.”

“It’s the connections that we’ve built over time, and the way that we’ve learned to work with each other, share our experiences with each other. I’ve learned so much from these women. They treat me like their own daughter.” Malik recalls the messages she received from some of the women checking in on her when the pandemic began to hit. “It’s that level of concern that I think is a beautiful part of this project,” she says. “l never thought that I was actually building it; it just happened.

What makes Malik’s work stand apart from others is that she portraits of women living in India, who are not allowed to leave their homes or in some cases do not feel safe even leaving their houses. In one of her works the woman not only conceals her entire face with embroidery, she then adds another layer by creating a veil, making her completely unrecognizable.

Long Way to Go!

Malik plans to resume the project in India, after restrictions of pandemic are over and continue this , ‘beautiful relationship’ to empower them in patriarchal society, to make them financially self- sufficient.

She firmly believes that international recognition of her work by British Journal of Photography has strengthened her resolve to take message of gender equality to its logical conclusion.

Comments are closed.